Photo by Frank Gavin Photography

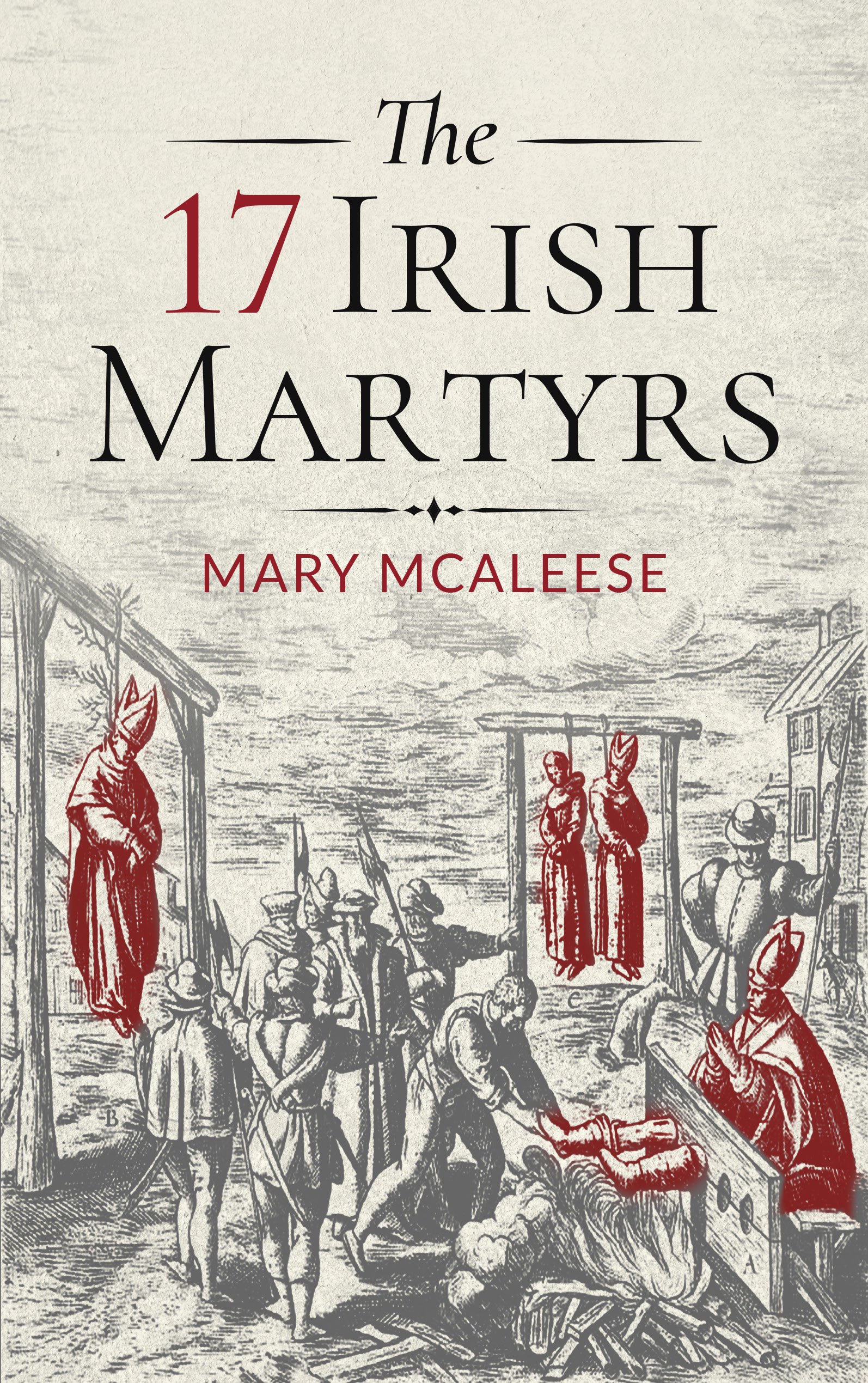

The 17 Irish Martyrs by Mary McAleese (Columba Books, 2022)

Thomas J. Morrisssey | The Irish Catholic

On September 27, 1992, Pope John Paul II beatified sixteen Irishmen and one Irishwoman. These are the 17 that Dr. Mary McAleese, sometimes President of Ireland, talks about in her latest book.

Each of them chose to die as a martyr rather than deny their faith in the teaching of the Catholic Church. They lived in the 16th or 17th centuries, times marked by fierce struggles over issues of religion and power. In Ireland, the English government decided to impose both Protestantism and political conquest on the predominantly Catholic population. In the resulting turmoil, hundreds of thousands of people died: among them hundreds of men and women who tradition remembers died solely for religious reasons.

In 1904 there was documentation of some 460 reputed martyrs. A tribunal was established to consider their sanctification case. After review, 257 cases were admitted for further review by the Sacred Roman Congregation of Rites.

Researchers

Over the years, some 80 researchers have worked on the material, producing around 40,000 pages. The task seemed endless. In 1936, the Roman adviser, Father Antonelli, suggested that they turn their attention to the strongest and best documented candidates.

In 1975, Dr Ryan, the Archbishop of Dublin, placed the work under the control of a special diocesan commission made up of a group of dedicated historical scholars. After years of working in archives across the Continent and across Britain and Ireland, the evidence has emerged for the 17 Irish people beatified by Pope John Paul II. Their stories are told here by Mary McAleese. His work is firmly based on the detailed reports of the Diocesan Commission and is presented in a lively style with historical imagination that captures the interest of the reader.

Candidate

The author takes care to place each candidate in its historical context. This is done most fully in the case of the first candidate chosen, Patrick O’Haly, the first Irish bishop to die for the Faith in Ireland. The history of the English Protestant Reformation is depicted from Henry VIII to Queen Elizabeth, and Spain’s role as the main Catholic power to which Irish rulers sought support.

O’Haly became an observant Franciscan and, while studying on the Continent, sought help from King Philip II of Spain for his friend James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald, who was planning an invasion of Ireland. Fitzmaurice landed with a small force, soon killed himself, and his enterprise failed. O’Haly asked for help for Fitzmaurice but took no part in any armed venture himself.

Appointed Bishop of Mayo by the Pope, however, O’Haly returned and eventually, accompanied by another Franciscan, Conn O’Rourke, was captured near the strong garrison town of Kilmallock, County Limerick. Both men refused inducements to abandon their religion in exchange for their lives and benefits, were savagely tortured, then hanged, quartered and quartered. Subsequently, their bodies were left hanging for several days at the mercy of mockery from government supporters.

Each of the martyrs were distinct personalities with their own particular stories. They were made up of two bishops, an archbishop, a number of men from religious orders, mainly priests, and six lay people. The lay people included four from Wexford – a baker, Matthew Lambert, and three sailors, Patrick Cavanagh, Edward Cheevers and Richard Meyler. Their crime was harboring and aiding a runaway priest who sought to escape to the Continent.

Refusing to deny their faith, they were hanged, dragged and quartered. The remaining secular victims died in prison for their religious beliefs, refusing any inducement to accept the Queen as head of the Church. They were from Dublin: Francis Taylor, a prominent citizen and former Lord Mayor, and Mrs. Margaret Ball, also a prominent citizen, who had two sons who became Lord Mayors of the city. One of the sons became a very bitter anti-Catholic Protestant. He imprisoned his own mother and left her to languish in misery and primitive conditions until her death.

The book has a helpful introduction which explains the meaning and role of martyrdom in Ireland and gives the history of research into the Irish martyrs from 1904 to the beatification of the 17 in 1992. Work on the remaining candidates continues.

There are some generalizations about the Irish people and their religious affiliation which disturb a historian, in particular the less than accurate comparison of the English population’s adherence to the new state religion in contrast to the “devoutly defiant” Irish, who were “made of different things”.

Historical material

The book is beautifully presented. Almost inevitably, with so much historical material, there are occasional omissions in the proofreading, but these minor flaws do not detract from the power and relevance of the story of these Irish martyrs.

Their relevance may seem remote to many in today’s Irish Republic, but today thousands around the world are still dying from persecution for their religious beliefs and echoes of the religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries. . still resonate in the northern part of our country, as well as in the Middle East and Asia.

A hallmark of the martyrs was their unconditional forgiveness of their persecutors. A true test of our Christian identity today, as the author observes, is to find loving forgiveness from past enemies, “to forgive the history we have inherited and build a new history where Christians ‘in fact love no matter what and in spite of everything”.

The 17 Irish Martyrs by Mary McAleese is available from Columba Books.