A Contested Past and its Legacy: Remembering the Troubles

Dianne Kirby

Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland

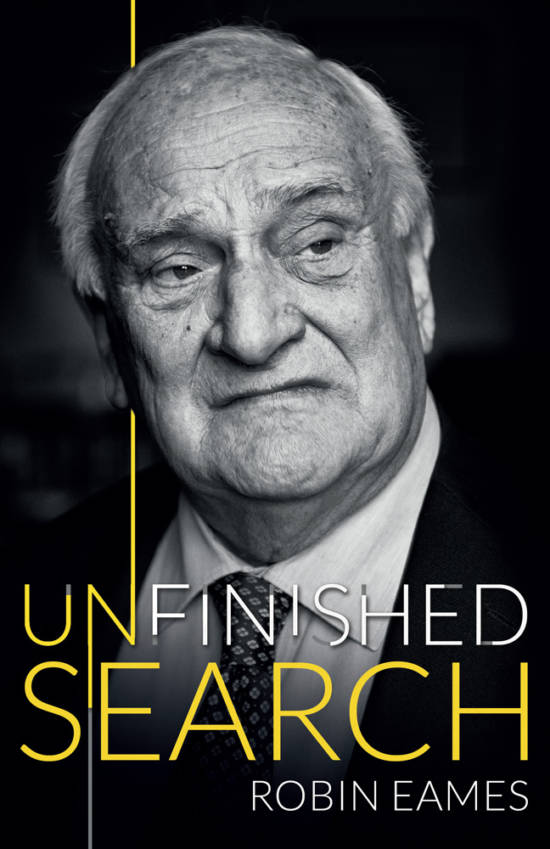

The significance of the Robin Eames book is not simply that it brings to the narrative the perspectives and recollections of a well-connected and respected leading churchman, but that it reveals how the pain and trauma of the conflict afflicted and remains with those at the top as well as those at the bottom. Eames was born in Northern Ireland. His father was a Methodist minister. Ordained in 1963, he first studied law before doing a theology degree. He was appointed Bishop of Derry and Raphoe in 1975 and translated as Bishop of Down and Dromore in 1980. He was elected Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland in 1986. An influential voice within the Anglican Communion, he held important positions of leadership during the conflict and the peace process. The book is not an autobiography. Eames’s life and work has already been well documented, as he acknowledges, by Alf McCreary.1 The book is rather a reflection on the Troubles, an attempt to come to terms with memories that he admits still have the power to overwhelm him.

Eames enjoys all the trappings of success in both his career and personal life, yet his remains a soul still haunted by the Troubles. Throughout the book, Eames returns to the same series of questions, repeatedly asking if, in essence, the churches might have done more. Whilst Eames was a latecomer to the peace process com- pared to Alec Reid, his was still a vital contribution to peace-building and maintenance. Eames is candid in discussing his attitudes to the unfolding conflict. A factor in his decision-making was undoubtedly his conviction that Northern Ireland was from top to bottom infected by a deeply rooted, ubiquitous sectarian disease (240). For Eames, Northern Ireland’s naked sectarianism had been ingrained over generations and would require generations more to erase. Interestingly, his view differs from that of some religious embedded in working- class communities. From their perspective, bad governance caused the divisions.2

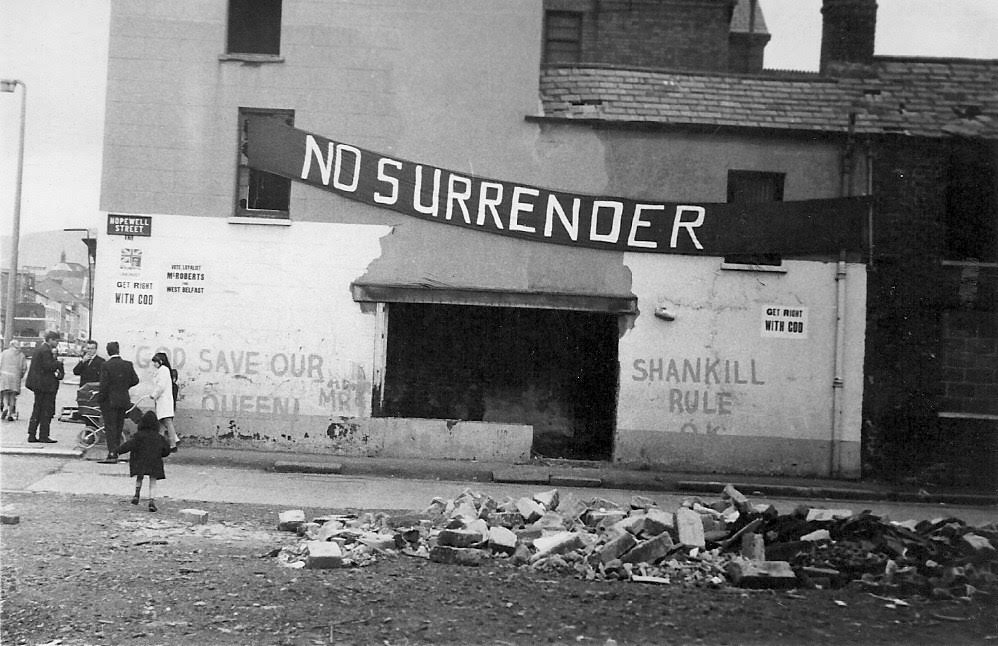

Eames readily recognizes the contradictory role played by the Christian churches. Among the many penetrating questions he raises, Eames crucially asks: ‘How far was religion itself a cause of the divisions in society and how far was the Church an active participant in keeping the divisions alive and well?’ (29). He frankly concedes and seeks to explain the reasons why the tendency was ‘to identify with victimhood within one community and that community was one’s own’ (66). He fully acknowledges that there ‘were figures who had a political religious identity which in its turn pushed forward the tribal sectarian identity which continued to be a feature of Northern Ireland life’ (137). His is less an attempt to mitigate than to recognize and render explicable the judgement of Methodist minister Sam Burch, who lived and worked on the Shankill Road. Burch observed: ‘In the early days, through the seventies and early eighties, the churches seemed impotent because we had allowed ourselves to become trapped in the political situation, being virtually tribal churches with tribal chaplains’.3 In 1988, over 200 men and women from across the evangelical Christian denominations acknowledged that they reflected societal divisions and as part of the disease were unable to be part of ‘the cure’. To become part of the latter, they agreed and highlighted 10 principles intended to contribute ‘to biblical thinking and action in Northern Ireland’.4 Most importantly, it was an evangelical recognition of their ‘share of the blame’, essential if they were to be part of an effective solution.

As with most religious in leadership positions, Eames consistently condemned paramilitary violence. In August 1994, he was approached by the Reverend Roy Magee for help in the discussions he had been holding with Loyalist paramilitaries. Eames was wary of being drawn into the conflict and being used by those he considered terrorists. With the IRA on ceasefire, he would only agree to talk with leaders who held the power to deliver a Loyalist ceasefire. During his meeting with loyalist paramilitaries, Eames invoked God and asked for a public acknowledgement of regret. He subsequently approached Prime Minister John Major for the assurances sought by Loyalists to enter the peace process. The outcome, on 13 October 1994, was a ceasefire by the Combined Loyalist Military Command accompanied by an expression of unequivocal regret for the distress caused by their actions. At a critical point, Eames engaged with the peace process and the risks it entailed. His account avoids the often confusing and ego-driven recollections of other key figures, offering a straightforward essentialist approach that provides profound insights into the challenges for those seeking a Christian course through a conflict in which Christians of one persuasion were killing those of another.

Primarily regarded as an ethno-nationalist conflict that could be explained by political and economic factors, religion was not regarded as causal. Nonetheless, during the ‘Troubles’, as the conflict was euphemistically termed, Northern Ireland’s churches were institutions with power and influence at all levels of society, at home and abroad, including amongst the secular. In the working-class and impoverished areas that bore the brunt of the conflict, Catholicism and Protestantism were cultural determinants in terms of identity and sense of belonging. More than simply a marker of national identity, for many their religion was also their political identity. Differentiating between the political and religious spheres was problematic in a state whose discernible hostility toward the Catholic Church was reflected in the denial of equality for its Catholic citizens. In addition to which, of course, there was clerical intervention in the political realm on both sides, most famously in the figure of the Reverend Ian Paisley, whose rhetoric embedded fear of the papacy and Rome into the Protestant-Unionist imagination. The combatants on both sides waged war in the name of their respective religious communities, regardless of institutional Protestantism and Catholicism condemning the murderous violence that scarred the small state for nearly thirty years.

- Alf McCreary, Nobody’s Fool: The Life of Archbishop Eames (London 2004).

- Des Wilson, The Way I See It (Belfast 2005).

- David Self, Struggling with Forgiveness: Stories from People and Communities (Toronto 2003), 67.

- For God and His Glory Alone (Belfast 1988).

If you would like to purchase this book, click here.

If you would like to purchase this book, click here.