Voices from the Desert: The Lost Legacy of Skelligs

Hugh MacMahon | November 2021

Google Maps are of little help when it comes to planning your future but I have found there are other reliable resources. In the on-going fog of uncertainty I was searching for my Christian roots in the hope of recovering a sense of direction when I came across Credo, a novel by the broadcaster and author Melvyn Bragg. In the ‘Afterword’ of his book he describes how he began an exploration of his own spiritual legacy when a student in Oxford reading History. His background was in the Church of England and the Celtic fringe of north-west England so he focussed on life there in the period 410-1066, known as the ‘Dark Ages’. He began to trace how Rheged, the area with which he felt a connection, became a land of saints, scholars, abbeys, gospels and crosses. Later the Celtic British tradition was to struggle for survival there.

Over the years he researched the period and wrote about it, finally bringing it to life in Credo (1996), a historical novel.

What caught my interest was the picture he painted of a distinctive Celtic Church, centred on spiritual search and monastic communities. The people portrayed showed similar ideals, insights and weaknesses as people today though they probably had a deeper spiritual sense. Their ‘Dark Age’ Christianity had an attractive simplicity and directness at a stage before theological disputes and legalistic concerns took over. I wanted to know more about it and turned in expectation to the writings of the early Church. However the manuscripts that have been preserved from then deal more with theological issues than the faith life that inspired them.

Where I finally found help was in Celtic monastic sites. Stone crosses from the 7th and 8th centuries had the image of two Egyptians, Anthony the Hermit and Paul of Thebes, alongside traditional biblical scenes. Where did such exotic figures come from and why were they included? I discovered it was because they were the pioneers of the Desert Father tradition that had inspired and moulded the early Celtic Church of Britain and Ireland. They had not been forgotten.

But what motivated those trailblazers, how did they spend their day and how did they justify their secluded existence?

When I visited Skellig Michael, a dramatic example of their life style off the coast of Kerry, I got more questions than answers. While one could not but admire the spirit of the monks who chose to live austere lives on that craggy rock, I wondered did it not cut them off from what I considered at the time a prime duty of Christians, that of service to others in society?

My search made slow progress until I came across the writings of John Cassian. In 376, along with his companion Gemanus, he visited monastic communities in the Egyptian deserts to interview the revered ‘Abbas’ there. His account, known as The Conferences, as well as his Institutions or Rule, were soon shared across Western Europe and came to define the shape Christianity was to take in the young Churches of Britain and Ireland.

Reading those Conferences which described the thinking, interests and daily life of those caught up by the ‘Desert Spirit’ not only answered many of my questions about them, it helped me reorient myself after the confusion of Vatican ll. It reaffirmed the solid sense of direction on which faith is built and features that do not change.

It also debunk the accusations that Christianity is essentially negative, other-worldly and suppressive.

Written in a modern question/answer format, the Conferences value human existence and fail to threaten hell fire. The Christian message is presented as an invitation. In describing the reasons for avoiding evil and seeking good, a comparison is made between a slave obedient out of fear, a servant seeking personal advantage and an attentive child seeking to return its parent’s love. The final motivation is the goal.

In their efforts to discover why people have difficulty in achieving this ideal, the Desert Fathers and Mothers examined the origins of tensions within the human psyche. Cassian’s master, Evagrius Ponticus, is credited with drawing up a list of the ‘Eight Principal Weaknesses’ that needed to be addressed. Later the number was reduced and become famous as the ‘Seven Deadly Sins’. It listed the frailties that had to be admitted and dealt with on an on-going basis. Otherwise there would be no progress.

Sin, therefore, is not as something to be measured and counted as if it were a ‘thing’ but the state of being separated from the source of love. The Elders’ guidance is positive, sympathetic and encouraging. It is a challenge to respond to the gift from the Father.

The discussions are lively and topics addressed include the purpose of life, the role of free will, levels of meaning in scripture, the structure of the human psyche, human weaknesses, relationships and the goal and methods of prayer. It is about living life to the full, not avoiding punishment.

Human sexuality is addressed in a straight-forward manner. Two of the Conferences discussed it so directly and unaffectedly that they were omitted in Victorian translations of Cassian’s work. The tension between the needs of the body and the soul were not ignored but the two were seen as companions on a journey who needed each other. The soul could not survive without the body and the body would have no purpose without the soul.

While the ‘Desert Message’ remains a classic guide for individual Christians it also provides an alternative vision to modern society.

The ‘weaknesses’ that the Desert Elders sought to moderate are now seen as ‘strengths’ to be encouraged. Over-eating, greed, envy and pride are now the drivers of consumer spending. Rather than controlling sexual instincts and anger, expressing them freely is seen as a healthy form of self-affirmation. The depression associated with a lack of purpose in life is accepted as inevitable and to be overcome with the help of drugs.

Not unexpectedly popular media either ignore the Desert Tradition or disparage it. However some misgivings are understandable and one is the question I myself had when I first visited the Skellig rocks. Was a life devoted to seeking perfection through isolation superior to a life devoted to service in society?

This issue features in a number of the conferences, usually in the context of the Mary-Martha story in the New Testament. When Jesus visited them, Martha performed a worthy service by preparing food for him and his disciples. Mary, meanwhile, was intent on gaining instruction and sat close to the feet of Jesus. When Martha complained and looked for Mary’s help, Jesus said, ‘Martha, Martha, you are anxious and troubled about many things but few things are needed. Mary has chosen the better part.’

In reporting on these discussions Cassian sympathised with the ‘Mary party’, he was addressing those thinking of cutting themselves off from society to concentrate on their weaknesses and experience love for and from the Father.

However Cassian himself, after his years in the desert, went on to be a peacemaker between disputing theologians, advisor to a Pope and founder of a monastery that was to influence civilisation in the western world.

Many of those trained in the desert tradition in Britain, Ireland and elsewhere, became teachers, bishops and community leaders in their own country and other parts of Europe. Others remained on to build on their initial experiences and became qualified to advise and guide the next generation.

The names of many towns and localities in Ireland begin with ‘Kil-‘, originally derived from the Latin for monastic cell. The lives of the ‘holy’ men and women who sought to experience the sacred there opened a wider world to the people among whom they lived. Even long after the saint’s death he or she continued to be reminders of what is positive, possible and lasting in life.

The desert Elders insisted that the calling to develop one’s spiritual instinct applies to all Christian, allowing for their individual circumstances. Generations have benefited from the inspiration and example of this ‘desert tradition’, many achieving a relationship with God that even the ‘Elders’ would envy.

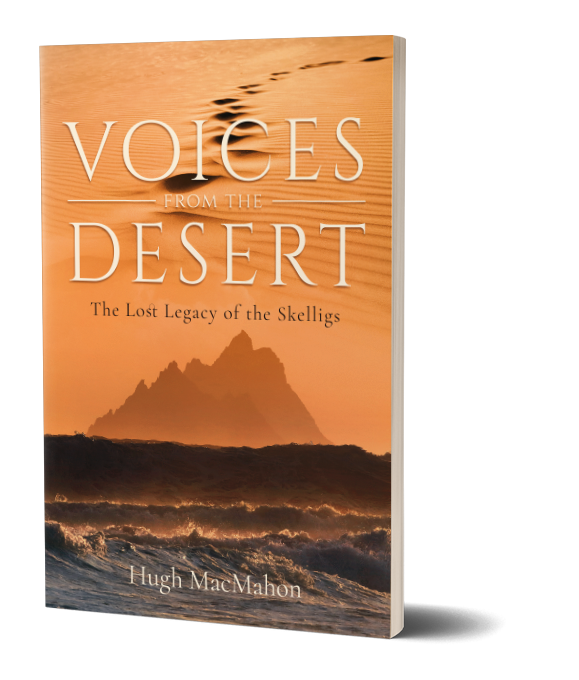

I found Cassian’s writing so helpful, simple and direct that I decided to jot down for myself the key questions in each conference and a condensed version of the Elder’s responses, preserving the original wording and reasoning as much as possible. To share them with others I added an introduction, comments on each conference and a review of the ‘Desert Legacy’. It is now in book form: Voices from the Desert: The Lost Legacy of Skelligs’.

The climax of Melvyn Bragg’s Credo is the Synod of Whitby when the Roman organisational vision of Church began to supplant the Celtic spiritual emphasis. Synods have historically marked a change of direction and perhaps the national synods now being planned will try to restore the balance between institution and spirituality by drawing attention to the legacy of the Desert Fathers and Mothers.

In the meantime, from the lakes of Rheged to the rough seas of Skelligs, enough reminders remain of the clear purpose to being a Christian.

The article first appeared on Independent Catholic News

VOICES FROM THE DESERT – THE LOST LEGACY OF THE SKELLIGS BY HUGH MACMAHON IS AVAILABLE HERE.

VOICES FROM THE DESERT – THE LOST LEGACY OF THE SKELLIGS BY HUGH MACMAHON IS AVAILABLE HERE.