‘Cardinal Keith O’Brien was like God to me. Then he tried to seduce me’: the whistleblower’s tale

As disgraced cardinal Theodore McCarrick faces trial in the US, an ex-priest tells of how he testified against the Scottish cardinal

Catherine Deveney | September 2021

As disgraced 91-year-old cardinal Theodore McCarrick stood in an American court last week, charged with three counts of indecent assault and battery on a minor, the spectre of the late Scottish cardinal, Keith O’Brien, hovered silently over proceedings. Two elderly men, who once donned scarlet robes and mitres, who reached the pinnacle of Catholic church power, stripped to civvies. McCarrick pleaded not guilty to the charges.

O’Brien, the UK’s then most senior Catholic cleric, and a vocal opponent of gay rights, resigned in 2013 after the Observer revealed details of his sexually inappropriate behaviour with priests in his diocese.

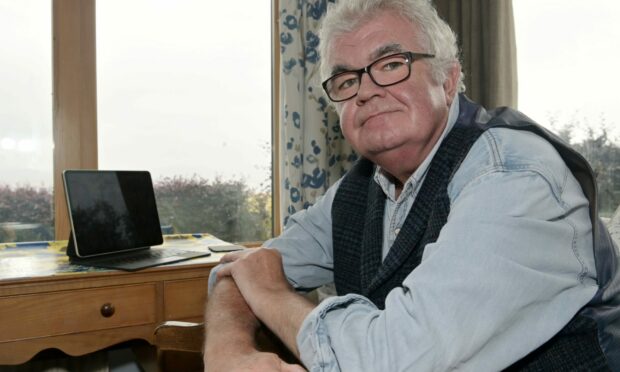

For ex-priest Brian Devlin, one of the four whistleblowers who testified against O’Brien back in 2013, the two cases are clearly linked. “If we hadn’t gone to the Observer back then, the church would have dealt with McCarrick quite differently. Without O’Brien, there would be no church process.”

Devlin has written a book, Cardinal Sin, outlining his experiences for the first time and describing his battle for improved church governance and accountability.

O’Brien was the first Catholic cardinal whose misdemeanours were dealt with publicly. He wouldn’t be the last. In a phone interview back then with the late Richard Sipe, a prominent ex-priest and psychotherapist who worked relentlessly on church abuse, Sipe rejected the notion of O’Brien as a single bad apple. “We have someone here too,” he told me. ‘It will go public soon.” That someone was McCarrick.

O’Brien’s case blew open the church door on accountability, forcing discussion where secrecy reigned. When Devlin and three serving priests made official complaints about O’Brien’s behaviour to the Vatican, silence had followed. Then Pope Benedict resigned. O’Brien was given permission to attend the conclave. Unwilling to accept the “business as usual’” message, the four went public.

Rome was forced to create a process. O’Brien was banished from Scotland but not stripped of his title. McCarrick has been. No longer Your Eminence, he appeared in court as plain Mr. Many of the accusations against him will not be heard in court because of time-bar rules, but he was expelled by the Vatican in 2019 after a church trial found him guilty of soliciting sex in the confessional and sexually inappropriate behaviour with both minors and adults.

Yet, his alleged misdemeanours – like O’Brien’s – were well-known internally, with church payments being made to victims as far back as the 1980s when McCarrick was Bishop of Metuchen, New Jersey.

Pope John Paul elevated him despite his history. Defrocking clergy culprits and casting them into the civil courts was a post-O’Brien tactic. Clergy misbehaviour was not new. The public knowing about it was.

The change has become a new form of Pontius Pilate handwashing. A spokesperson for Newark archdiocese refused to comment on McCarrick in the American press, saying it would be inappropriate because “he is now a private individual who is no longer affiliated to the archdiocese”.

The scandals have rocked – and changed – Catholicism. New processes. New guidelines.

But it has been lip-change, not heart-change – what Pope Francis calls, “the cult of appearance”. Not deep enough or fast enough, says Devlin, who waived his anonymity to write his book. “People go with sincere feelings to their bishop and he doesn’t respond. It’s indescribably bad and has nothing to do with Christianity. They still hurt and control people and I demand my freedom to say, ‘Stop this. Stop your cruelty.’”

It is difficult to explain the gulf between the public and private faces of the Catholic church, the covert connections between silence, secrets, abuse and cruelty. But the laity’s obedience is being replaced with a new cynicism.

Devlin left the priesthood in the 1980s because he could not work with O’Brien, who had been elevated to archbishop. Back then, his mother was devastated. Salvation was tied up in her priest son. Now 91, her response to his book is telling. “Brian,” she warned him, “check your brakes every morning before you drive your motor.”

Unlike McCarrick’s alleged crimes, O’Brien’s centred only on adults. After the scandal came compassion – for the perpetrator. He was the sinner in all of us, the poor old man who had lost everything through human frailty. It was sad, and it was true. In a power-based church with an eye-popping bank account, earthly losses were understood. Less understood were the spiritual losses of those whose victimhood was publicly accepted by the church through clenched teeth, but who were privately dismissed as conspirators and clypes (the Scots word for a telltale).

“Keith O’Brien stole from me,” says Devlin, “He stole any notion of God and spirituality that I had.” Devlin was a 19-year-old seminarian when O’Brien groomed him, seducing him into friendship before attempting to seduce him sexually – advances that Devlin rebuffed but which shook him to his core.

“You have to understand O’Brien’s position in the seminary. He was my spiritual director. Talking to him was like talking to God. He was there in all my weaknesses. He used his charisma and charm – and he had plenty of both – to convince me I would be a good priest.

“I thought he was the holiest man I ever met. When he did what he did, the whole edifice started to unravel.”

The morning after fleeing O’Brien’s drunken advances, Devlin watched him on the altar. “I remember that moment so clearly. I looked at him and thought: you are a fraud. I could see it was a cosmetic exercise, this holy-man image. The bonhomie, the jokes, the banter … all of it was a con trick to hook me, and I imagine others, into an intimacy with him.”

He couldn’t report O’Brien. He was confident that he would be dismissed rather than O’Brien: “Power abuse begins in seminary.”

Only after discovering other victims over 30 years later – via Facebook – did he talk.

Devlin does not hate the Catholic church. It shaped him. Nor did he hate O’Brien, who died in 2018 at the age of 80. But the church belongs to the people, and they must now wrest control from the O’Briens and the McCarricks who cynically abuse power.

The clergy, he insists, are poisoning the church well – not the laity. “Clericalism is rampant and we need to speak out. I will never, ever be silenced in my pursuit of what I think is authentic about being a Catholic.”