St Patrick was a gentleman; he came of decent people;

He built a Church in Dublin town, and on it put a steeple.

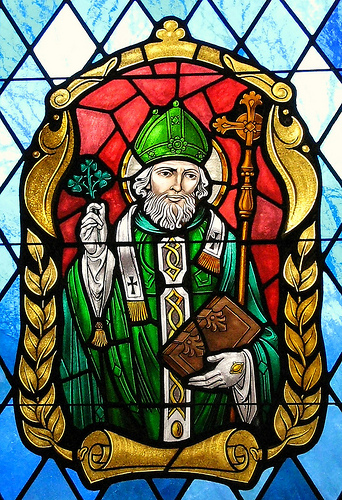

St. Patrick (Source: Library of Congress, 1872)

Perhaps the most famous representation of St Patrick of Ireland is an engraving made in 1642 by Fr Thomas Messingham. Versions of it dating from the early twentieth century present Patrick as tall and venerable, robed in green vestments, holding up a shamrock as a catechetical aid before King Laoghaire or pointing down to the water at his expulsion of the snakes. When historians got to work on this image they showed that the story about the shamrock dates only from the seventeenth century and the one about the snakes probably dates from Viking times, around the year 1,000.

Although these legends are not historically factual, they do expose truths about St Patrick: the Trinity was central to his life and teaching; and while he may not have encountered snakes in Ireland such as the ones you see in the zoo, he did expel the evil that is symbolised by the snake.

Facts of history

But what historical facts do we know? Well, we know that St Patrick existed and roughly when – namely, the fifth century AD. We know ‘that he was a bishop in Ireland; that he came from Britain where his father had been of the Roman official class and well-to-do.’ We know that he devoted much of his life to evangelising the Irish people, baptising them in large numbers. However, the most real and rounded Patrick emerges from the pages of his own writings. Two of these survive, the Confession and the Letter to Coroticus. Together they make up about thirty pages of a modern book. But they are full of information, mainly about ‘his character, his faith, his vision, his understanding of God’. From the two documents it is evident that we are dealing with an able and well-informed man.

His life is enveloped in the consciousness of being under orders from Christ to bring the gospel to the Irish. This is the basis of his unflinching steadfastness and confidence as he faces criticism of his mission. His genius often comes across, not directly in what he says, but in what he means – a characteristic readily understood in Ireland.

Patrick’s exact place of origin continues to baffle scholars. England, Scotland, Wales, and Boulogne-sur-mer in France, have all been mentioned. He was born into a Christian home, and presumably for a good grounding in the faith. But in his own honest way he admits that in his teens he and his companions didn’t pay any great attention to the advice of the priests, and in later years he regretted this.

The first serious crisis in his life occurred when he was kidnapped and sold into slavery in Ireland at the age of sixteen. From his writing, one can glean that his family were, materially speaking, fairly comfortable. Now in exile, he was anything but, as he found himself alone in a herdsman’s shed or under the open canopy of heaven. Curiously enough, it was in these surroundings of isolation that he matured in his faith. With all the time in the world to think, and the silence and the darkness of the night around him, he came to realise that in all the upheaval there was one constant element: God.

Many years later, in his Confession, he wrote:

My faith grew stronger and zeal so intense that in the course of a single day I would say as many a a hundred prayers and almost as many in the night. This I did even when I was in the woods and on the mountains. Even in times of snow or frost rain I would rise before dawn to pray. I never felt the worse for it; nor was I in any way lazy because, as I now realise, I was full of enthusiasm.

After six years in slavery, Patrick made a successful bid to escape. He walked about two hundred miles across Ireland until he found a trading ship bound for the continent. After some initial disappointment, he was taken on board, and after three days at sea landed in the west of France. He finally made his way to his relatives in Britain but not before enduring a further two months of captivity.

Now that he was home, his relatives wished him to stay, but Patrick, in a dream, heard ‘The voice of the Irish’ calling him to return and walk among them once more. With that generosity of heart characteristic of the man, he studied for the priesthood, was later ordained bishop, and sent on a mission to Ireland. For this he was well fitted, for besides his religious formation, he had from his slavery days, a knowledge of the language and customs of the Irish.

Now that he was home, his relatives wished him to stay, but Patrick, in a dream, heard ‘The voice of the Irish’ calling him to return and walk among them once more. With that generosity of heart characteristic of the man, he studied for the priesthood, was later ordained bishop, and sent on a mission to Ireland. For this he was well fitted, for besides his religious formation, he had from his slavery days, a knowledge of the language and customs of the Irish.

His missionary career was spectacular. True, he wasn’t the very first to bring the Christian message to Ireland, but his coming was highly significant. Without brag or boast he sets out the facts of what happened. He tells us that he ‘baptised thousands’, ‘ordained clerics everywhere’, ‘gave presents to kings’, ‘was put in irons’, ‘lived in daily expectation of murder, treachery or captivity’, ‘journeyed everywhere in many dangers, even to the farthest regions beyond which no man dwells’, and rejoiced to see ‘the flock of the Lord in Ireland growing splendidly with the greatest care and the sons and daughters of kings becoming monks and virgins for Christ.’

Kyrie Eleison and Deo Gratias

One of our most ancient manuscripts, the Book of Armagh, tells us that Patrick wished the Irish to have two phrases ever on their lips, Kyrie Eleison and Deo Gratias; Lord have mercy, and Thanks be to God. It was between these two prayers that Patrick lived out his own full and saintly life. It is where we, too, will find the fullness of life – trusting in the forgiveness of the One who loves us, and eternally grateful for everything.