Today is the feast day of French saint Joan of Arc, considered a national heroine of France for her role at the young age of 18 in the Siege of Órleans helping to provide a decisive victory over the British. An awe-inspiring woman who led armies and died for her faith, Joan of Arc was a martyr – burned at the stake as a heretic by British and their French collaborators. More than 500 years after her death, she was canonised by Pope Benedict XV as Roman Catholic Saint Joan of Arc on the 16th of May 1920.

Since the very first Christian martyr Jesus of Nazareth, people have been sacrificing themselves for their faith. Whether religious, political, or social, Christian martyrs have a powerful sway over the public’s imagination. Their sacrifices give their messages power and meaning, and give them a life far beyond their tragic ends. Ireland throughout its bloody history has has its fair share martyrs and what could be more inspiring than sacrificing yourself so that others may observe be free to observe their religion?

However, there are countless stories of martyrdom that never receive due recognition. There are many well-known martyrs such as Joan of Arc but what about Irish martyrs? Little is known about the Irish martyrs of the 16th and 17th centuries. In a time of widespread religious persecution spanning over two centuries only 17 Irish people became beatified. Why? What made these people so special? What made them worthy of canonisation?

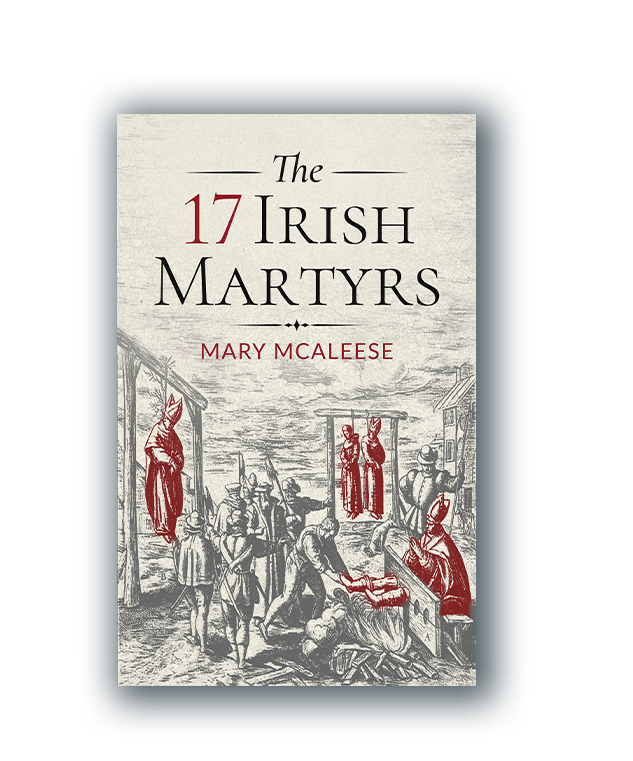

Former President Mary McAleese has delved into Irish history to answer just that. Her new book, The 17 Irish Martyrs highlights the real lives these people led and what made them so special. Historically, Ireland’s shores have been no stranger to bloodshed for faith, here is an extract from McAleese’s book detailing the lives of Patrick O’Healy, O.F.M. and Conn O’Rourke, O.F.M. martyred in 1579.

The 17 Irish Martyrs by Mary McAleese €16.99

History is selective about the memories it cherishes. Generations of young Catholic Irish people today are familiar with the story of the martyrdom of St. Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh, who was executed at Tyburn in 1681. Yet in many ways his was the end of a much longer story, for he was the last Irish Bishop to die for his faith during more than a century of violent religious repression. The first was

History is selective about the memories it cherishes. Generations of young Catholic Irish people today are familiar with the story of the martyrdom of St. Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh, who was executed at Tyburn in 1681. Yet in many ways his was the end of a much longer story, for he was the last Irish Bishop to die for his faith during more than a century of violent religious repression. The first was

Patrick O’Healy, Bishop of Mayo.

It is sobering to reflect that if Patrick O’Healy were to find himself suddenly transported to twenty-first century Europe, he would have little difficulty in updating himself on certain contemporary problems. From the Troubles in Northern Ireland, to the assertion of Catalan identity, there would be little that would be unfamiliar to his eyes. For this holy man of outstanding intellect and spirituality was as much at home in the harsh wilds of County Leitrim as he was in the opulence of the Spanish Church.

Experts differ on the precise place and date of Patrick O’Healy’s birth, but he entered the world around 1543, probably in County Sligo in north-western Ireland, where the O’Healy clan (O’hEllidhe in Gaelic) was strong. Patrick O’Healy was destined to become one of the most celebrated of the martyred recusants. He entered the priesthood shortly after Elizabeth became Queen and he had few illusions about the difficult life he was undertaking. O’Healy was drawn inexorably into the climate of intrigue. A committed and educated Counter-Reformationist, he saw Ireland as an important battleground and he wanted to play his part. He was a passionate man of exceptional rhetorical skills. He began to put them to use for Ireland. By 1575, he was actively involved in trying to persuade the Spanish king and the Pope to help the cause of Catholics in Ireland. In Paris he found the travelling companion who was to accompany him all the way to martyrdom, Conn O’Rourke.

Whether accident or design brought these two men together is impossible to say. Conn O’Rourke remains one of the most mysterious and enigmatic of the martyrs. Like O’Healy, he was from the Province of Connacht and had joined the Franciscans in Dromohaire some years after O’Healy had left for Spain. He was about six years younger than O’Healy but would certainly have heard of the latter during his novitiate at Dromohaire.

Following in the footsteps of O’Healy, Conn O’Rourke had gone abroad to continue his studies. With so much in common, and with O’Healy’s hunger for up-to-date information about his homeland, it is possible to imagine the bond which developed between the two men. O’Healy had been away from home for many years. Here was a confrere right up to date on the situation and presumably with knowledge of the many friends O’Healy had left behind in Dromohaire and in Sligo.

The two priests were taken to Limerick where they were subjected to a series of heavily biased interrogations by Drury, acting under martial law they were easily apprehended and quickly imprisoned in Kilmallock. Only weeks after their capture and death, the Earl of Desmond was writing to the Tudor authorities, claiming the full credit for having had them arrested and interrogated. They were asked to acknowledge Elizabeth as Supreme Head of the Church, but both refused to do so, insisting that the Pope alone was head of the Church. The interrogation went beyond robust questioning. Bishop O’Healy was severely tortured. Drury offered to give him full recognition as Protestant Bishop of Mayo, with all the financial and social benefits which would follow naturally from such an appointment, if he would deny the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church. O’Healy replied that he would accept death rather than turn his back on his faith.

Shortly before the hour of execution, Bishop O’Healy asked if he and Fr Conn O’Rourke could be given permission to pray together. It was granted. Beneath the gallows they devoutly recited the litanies and then gave each other absolution.

Inevitably, as the first Irish bishop to die for the faith in Ireland, O’Healy became a legend. Over the centuries his story was told and retold in histories and martyrologies, never quite the 17 Irish Martyrs fading into oblivion. Four centuries later a new generation of Catholics re-examined his life and found a story worth retelling in an Ireland still trying to heal the legacy of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. These two men were the first of the seventeen Irish martyrs.

The 17 Irish Martyrs by Mary McAleese is available in all good book shops and at Columba Books.