Ireland celebrates National Holy Wells Day on Sunday, June 14th, 2020! Our recently released book ‘Journeys of Faith: Stories of Pilgrimage from Medieval Ireland’ by respected medieval archaeologist and expert Dr Louise Nugent contains many interesting references to Holy Wells around the island. Many hundred years ago, these sites attracted pilgrims from near and far, seeking healing and redemption. Two such famous holy wells are located in present-day Co. Carlow and Co. Down. These are but snippets taken from this amazing book that reveals the medieval lives of our ancestors.

Penitential Bathing at Tigh Moling

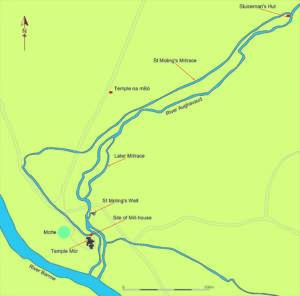

Plan of medieval pilgrim landscape at St Mullins.

Credit: Johnny Ryan

Tigh Moling, a monastery on the banks of the River Barrow in Co. Carlow, is one of the best-documented medieval outdoor pilgrimages in Ireland. Founded in the 7th century by St Moling Luachra, it sits in the centre of the village of St Mullins.

The early pilgrimage was probably focused on the grave of St Moling, who died and was buried there on 17 June 696/697. From the 10th century, an extensive pilgrim landscape that included a spring well and a millrace, filled by water diverted from the Aughavard River, had developed around it.

Pilgrims were well aware of the many miracles the saint had performed during his lifetime. His grave must surely have been sought out in early centuries. In 1323, we are told that the church of Tigh-Moling and its relics were burnt by Edmund Butler1. The loss of these relics did not affect pilgrimage, as the sturdier relics – the millrace and holy well – remained unharmed and have survived to the present.

St Moling’s holy well is a large pool filled by a natural spring. Its waters flow into a small early stone chapel. The well’s water flows through the east gable of the church from two holes in large granite slabs. The holy waters cascade onto a stone front, before falling directly onto the paved granite floor.

St Molings’s holy well, St Mullins, Co. Carlow

The well chapel is a very rare early medieval baptismal chapel. Its primary function was the sacrament of Baptism2. The waters of the well are associated with healing, and the 10th century Irish Life of St Moling recalls that the saint’s eye was healed with water from the well brought to him by an angel, who blessed the well and its waters3.

The Latin Life of St Moling, written in the late 12th/early 13 century, recalls how the saint single-handedly dug the millrace over seven years. When his work was completed, he consecrated it by walking through it. More importantly, the Life tells us that the saint promised to intercede on behalf of all who subsequently walked through the water.

St Molings’s holy well, St Mullins, Co. Carlow

In 1348, the millrace was the focus of a mass pilgrimage, in response to the Black Death, with men and women desperately washing and praying in the waters of St Moling’s millrace and holywell4.

For medieval pilgrims, the narrative of the millrace at Tigh Moling was more than its association with St Moling. In the Irish Life of St Moling, the saint’s millrace is equated with the ‘locus of Christ’s baptism’, and identified as a ‘branch of the river Jordan.’5

The wading or ritual washing undertaken at Tigh Moling may be inspired or even modelled on the rite of baptism administered by John the Baptist in the River Jordan to the people from Jerusalem. The religious of Tigh Moling now placed the River Jordan in their own landscape, allowing Irish pilgrims to have similar experiences of physical healing and spiritual rebirth without traveling halfway across the world.

To learn more about the pilgrimage site at St Mullins, Co Carlow, visit the author’s own blog here.

Washing away Sins at Struell

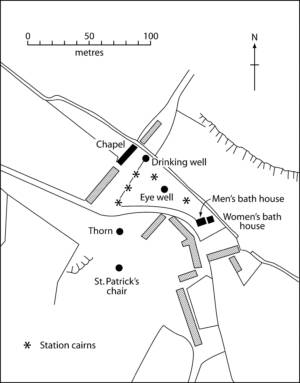

Map of the pilgrimage landscape at Struell, Co. Down.

Credit: Findbarr McCormick

The holy wells of Struell in Co. Down were part of a cluster of Patrician pilgrim places, which include Patrick’s grave and relics at Downpatrick and the nearby Saul Abbey, places that were visited by medieval pilgrims. Struell was once a bustling pilgrim destination in summer months, until the time of its suppression in the late 19th century. Thousands of people are said to have made a pilgrimage to this place for midsummer.

Today, Struell is a quiet peaceful spot, with the ruins of a small church, two holy wells called the Drinking Well and the Eye Well, two bathhouses – all overlooked by a rock outcrop known as St Patrick’s Chair.

Struell first appeared in the early Irish poem know as ‘Fiacc’s Hymn’, written in honour of St Patrick, c.800, and recorded in an 11th–12th-century text called the Liber Hymnorum. The poem tells the origin story of the holy wells. St Patrick was said to have prayed at one of the wells and to have immersed himself in its waters while reciting psalms. He then slept on a stone, perhaps an early reference to the outcrop known as St Patrick’s Chair.

St Patrick’s Chair at Struell, Co. Down

The cold of the weather used not to keep him from spending the

night in pools:

He strove after his kingdom in heaven; he preached by day on heights.

In Slane [Struell] north of the Benna Bairche – neither drought nor flood used to seize it – he sang a hundred psalms every night, he was a servant to the King of angels.

He slept on a bare flagstone then, with a wet quilt about him:

His bolster was a pillar-stone; he left not his body in warmth.

The fact that the wells and holy stone are mentioned in the hymn suggests that both had a religious significance and were seen as holy places at the time the poem was composed. In more recent centuries, the Drinking Well still retained a folk tradition that it was the very the spot in which Patrick had immersed himself in the water.

Journeys of Faith: Stories of Pilgrimage from Medieval Ireland by Louise Nugent is available here.