Dry humour and deep thinking from a radical monk

David Burke’s Bookshelf – 07/07/21 issue of The Tuam Herald

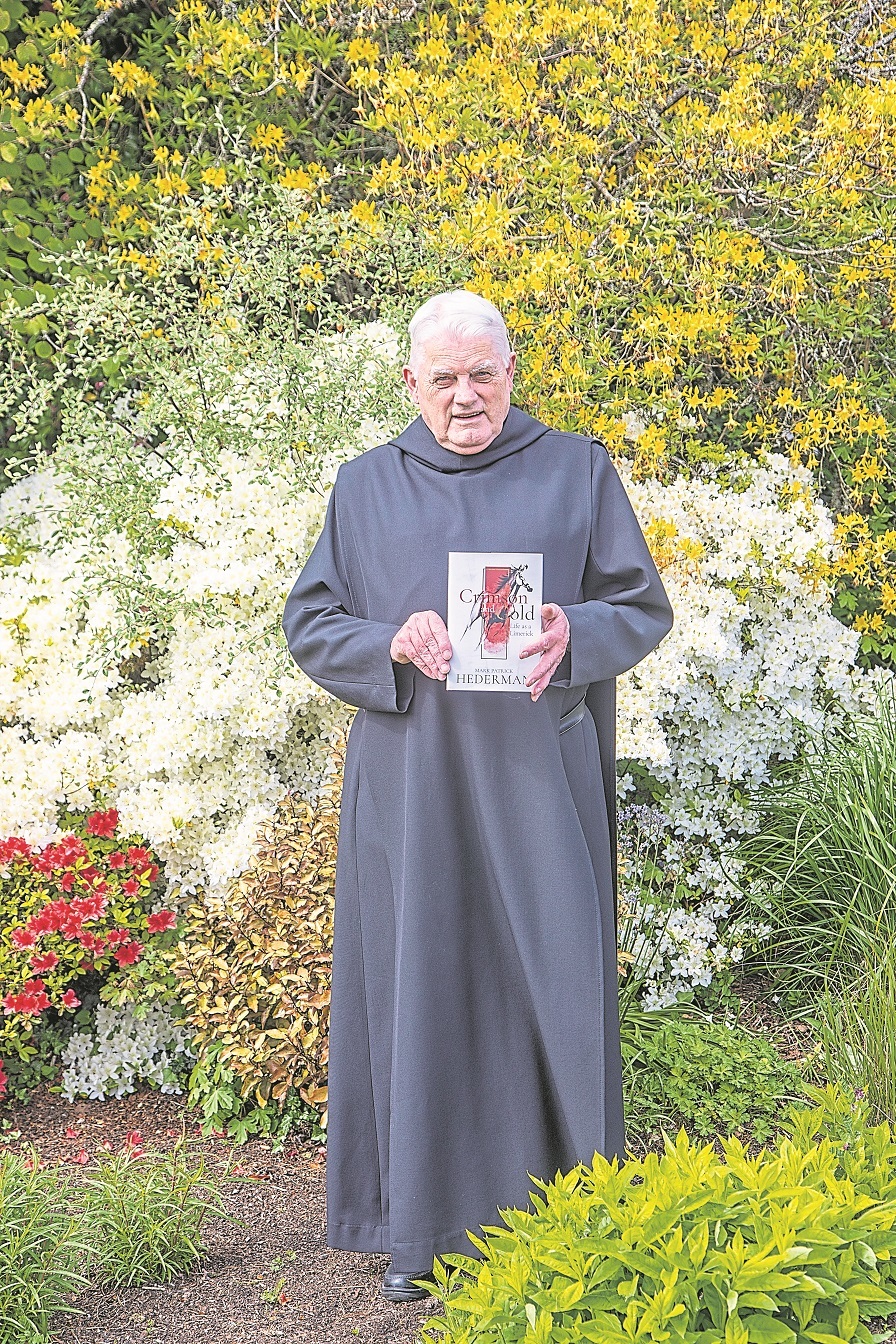

When Mark Patrick Hederman was less than ten years old he had a mystical encounter with God, to whom he pledged eternal allegiance. That spiritual event turned him into a precocious child who later became one of the most extraordinary monks this country has ever sheltered, and probably the best known of modern times. A member of the Glenstal Abbey Benedictine community from his schooldays, his sonorous voice will be heard from time to time on the radio as he elucidates some point and he has the gift of making the most obscure theological issue seem utterly clear, at least while he is explaining it.

There is plenty of theology in his latest book, but let that not put any reader off. In a most unexpected blend of biography, social observation, Irish and Catholic church history, psychology and

theology — not to mention dry humour — he by turns informs, amuses and educates his reader and invites him or her to ponder deep truths. His unconventional thinking was nurtured by an unconventional upbringing — in Irish Catholic terms at least.

Though the name sounds German, Hederman derives from the Irish Ó hÉadroman, or lightfooted man. It originated in Co Clare, and legend says the first Ó hÉadroman was a ferryman for St

Senan. His branch managed to hold on to their lands despite not changing their religion, so Mark was born into a family of West Limerick “gentry”, most of whose friends were Protestant.

He did not attend school until the age of nine. This was because his American mother felt that children should not go to school until they wanted to.

The subtitle of the book is Life as a Limerick. The Limericks in this case are the Limerick Hunt, although the literary form comes in for attention later. He tells some fascinating and hilarious stories of the various upper-class types who populated his youth, some homegrown, others blow-ins from England. Escaping a Labour government, they created a short-lived world of glamour and excitement. They had their pecking order: for those without titles, army rank determined the order of precedence: a brigadier outranked a colonel who in turn was above a major. This determined when they would shoot at the game birds being driven their way.

This portrait of a class leads neatly into a chapter titled The New Aristocracy. And guess who they were: the quote “A pump in the yard, a bull in the field, a son in the priesthood” says it all. There was immense pressure on young men to become priests, and for decades the fear of being labelled a “spoiled priest” kept many an unfortunate behind the seminary walls.

This portrait of a class leads neatly into a chapter titled The New Aristocracy. And guess who they were: the quote “A pump in the yard, a bull in the field, a son in the priesthood” says it all. There was immense pressure on young men to become priests, and for decades the fear of being labelled a “spoiled priest” kept many an unfortunate behind the seminary walls.

After ordination the pressure continued. With the consecration the central point of the Mass, the only channel for Jesus Christ to be present in the world, the priest in the words of St John Vianney “has the keys to the heavenly kingdom”.

Hederman says such total reliance on priestly hands “bred two kinds of pathology, one in the priest, the other in the people”. The priest is overwhelmed by his responsibility to provide such salvation during every waking moment of his life; the people regard him as a limitless resource on which to ventilate their fears and anxieties.

However, over a year of lockdowns, he says, has taught us that God does not need anyone’s hands or anyone’s ministry to reach out and touch one of God’s people.

For centuries the church has consisted of a hierarchy from the pope down, with even cardinals divided into three classes. Not that different from the West Limerick “gentry”. Furthermore, with the

decreasing influence of the church and the decline in vocations, he asks where is God to be found in the Ireland of today, adding that we are experiencing a spiritual famine. The answer is for the

people to reclaim the sense of being Church. It should resemble more the church of the first millennium, an inverted pyramid in which the People of God are primary and priests and prelate must exercise their leadership roles in service and together with others.

While Hederman’s is a radical voice, there is no doubting his dedication to what he calls his “lifelong and obsessional search for God”. He believes the Holy Spirit spoke to him during his childhood experience on Knockfierna (the Hill of Truth) in the shadow of which was his home.

Likewise, when he was elected Abbot of Glenstal, a position he did not want or seek, the Holy Spirit must have animated his fellow monks in their two-thirds vote. True to his maverick nature,

Brother Mark Patrick reluctantly agreed to being ordained a priest in order to fulfill the requirement for the office of Abbot.

His book is a sometimes confusing mélange of subjects, but its essential purpose is to drive along the search for God. It is a deceptively easy read in places, plunging into the profound when least expected, and it is very worthwhile for anyone who wants to be both entertained and stimulated.

Crimson and Gold: Life as a Limerick by Mark Patrick Hederman