Long ago, a little girl grew up near Slemish Mountain (Sliabh Mis), in pagan Co. Antrim in Ulster, the northeast of Ireland. This girl was named Brónach. Her name, rather unusually, meant ‘sorrowful’. It wasn’t a common name and Brónach, even from a tender age, was determined not to let it decide her fate in life! She didn’t want to be sad and sorrowful.

From time to time, Brónach was plagued by strange dreams and visions, at night and even while awake. Some of these dreams were repetitive and began when she was young. Dreams were powerful things, and were always to be taken heed of. In these dreams, Brónach fought one of the most powerful Irish gods, a member of the Tuatha Dé Danann – Manannán mac Lir (Son of the sea).

Kenneth Allen/Manannán mac Lir sculpture Gortmore/CC BY-SA 2.0

As a young girl, Brónach lived nowhere particularly near the sea, so she pondered those dreams long and hard. What could they mean? Manannán was known as a powerful warrior and King of the Otherworld in Irish mythology. In pagan Ireland, for those who followed druid beliefs, he was a god to fear on the seas, as your life was in his hands. He rode across the waves with his chariot, led by his horse Enbarr, who could cross both land and sea, swifter than the wind!

Brónach’s father was an important man. His name was Míliuc mac Buan, better known as Milchú. He was a chief of the Dál mBuain, mainly in Co. Antrim in Ulster. What is key to our story is that Brónach’s father, Milchú, was the man who kept the great St Patrick in slavery as a boy at Slemish mountain, Co. Antrim. Years later, after Patrick escaped from slavery, he returned to Ireland. Tradition has it that Brónach and her brothers, Gall and Guasacht, along with her two sisters (both called Éimhear) all heard the gospel and became Christians the time they heard Patrick speak. Since he was back in Ireland, he probably went to Milchú’s home to convert him and his family. Brónach’s life was forever changed. Indeed, her brother Gall became a priest and later a bishop in the area of Dromore, Co. Down. And her brother Guasacht was appointed the first bishop of Granard in Co. Longford by St Patrick. Her two sisters were also church leaders (perhaps at Clonbroney, Co. Longford)!

Meanwhile, Brónach had more dreams when she slept, and visions while awake. She dreamt that, like her brothers and sisters, she became a church leader and started a church. But where to locate her church? Where did God want her to go? Then she remembered her recurring childhood dreams of Manannán mac Lir, the Sea God. Perhaps she should set up that church near the sea and look after sailors and fishermen? The local people all believed that Manannán mac Lir was a god, and so would decide if they lived or drowned at sea. Brónach needed to tell them the truth, which is that God from the Bible would take care of them, even at sea!

Brent Goose. Photo: Andreas Trepte/Wikimedia Commons

Then, Brónach had further dreams and visions of hundreds and hundreds of Brent Geese (Cadhan in Irish). These were light-bellied brent geese, to be precise, and they were flying past her. But one was at her feet. She would wake up in the mornings, her head still filled with their honking sounds (called a ‘trill’). Brrrrrllppp, brrrrllppp, brrrrup, brrrup! On and on they honked those sounds in repeat.

She knew her brent goose dreams were significant as, in Celtic Christianity, the wild goose is a symbol of the Holy Spirit. This came from days when the Greylag Goose (Gé ghlas in Irish) represented the Holy Spirit. The Greylag goose lived at Brónach’s home, as well as the rest of Britain. Over time, any wild goose species represented the Holy Spirit. Now, Brónach knew the brent geese overwintered in the loughs of Co. Down (both Strangford Lough and Carlingford Lough), so which lough should she go to?

Then she had another dream, of walking past the huge Cloughmore Stone near Rostrevor, Co. Down, to the south of the Mourne Mountains. Everyone in Ulster at that time knew the story of how it got there. It was a huge granite bolder, sitting on the slopes of Slieve Martin Mountain that overlooked the forests of Rostrevor and Carlingford Lough. The giant, Fionn mac Cumhaill (Finn McCool), had been having a battle one day with another giant, and thrown it at him from the Cooley Mountains in Co. Louth, all the way northwards across Carlingford Lough! Some say that the other giant was the Scottish giant, Benandonner; others say it was a local frost-giant named Ruiscairre. The locals rightly called the Cloughmore Stone ‘the big stone’.

Well, that settled it. God’s plan for her was to set up a church near Carlingford Lough. Through her dreams and visions, and even little ‘pictures’ in her head, God had left a trail of pebbles for Brónach, like in the Hansel and Gretel story, to find the way to her new home. One of these pebbles was even a huge, 50-tonne bolder!

Carlingford Lough. Photo: Keith Ruffles/Wikimedia

So Brónach lived beside the stormy waters of Carlingford Lough, on its north side in what is now Co. Down. She started a church for the local people and chose a beautiful site right under Slieve Martin Mountain and the Cloughmore Stone of her dream. It overlooked a lovely river and glen. Its old name was Glen Sechis (‘the Glen of Seclusion’), so it was a perfect place to meditate on God. In the future, it would be named after her – Cell Brónche (‘church of Brónach’), now Kilbroney.

Today, the modern village of Rostrevor is beside it.

So, how does Brónach’s bell come into the story? Well, you will have to read the full story to know all the details! But…she had one made and used it to warn sailors of danger on Carlingford Lough. Soon she had a church full of grateful fishermen and their families. What became of her famous bell? There is a story that for hundreds of years after the church, a bell could be heard ringing on stormy nights. Locals remembered that it must still be a warning to seafarers on Carlingford Lough. Then in the 19th century a bell was found in an old oak tree after a storm one night! Though it dates to 900 AD (and so can’t be Brónach’s actual bell) it can be seen at the nearby Star of the Sea Church, Rostrevor. If you visit the church, a striker rings the bell for you so that you can hear it! It sounds a perfect pitch ‘D’.

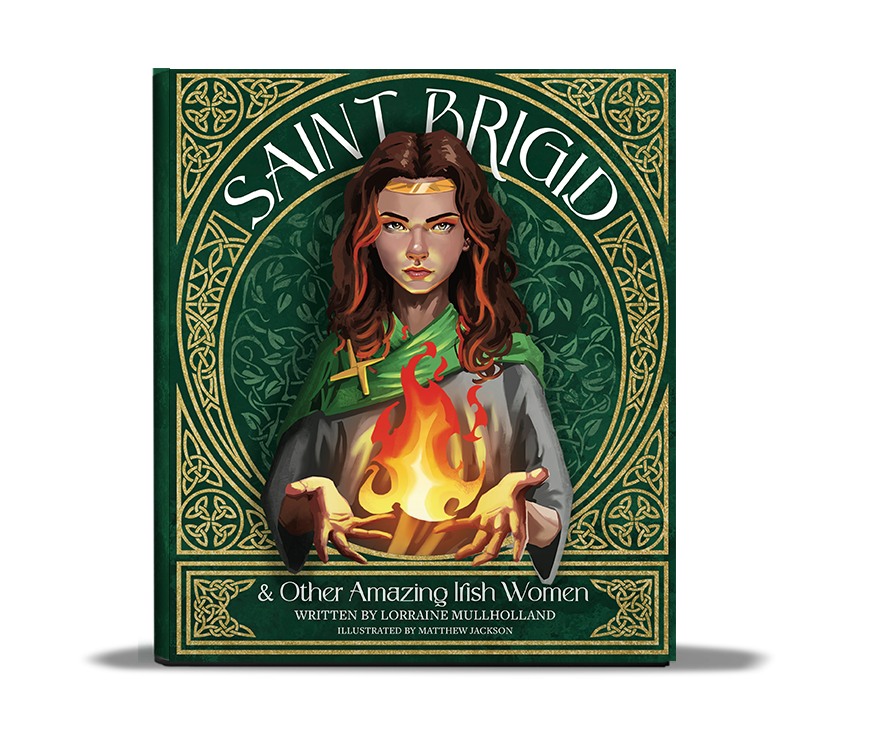

This is an excerpt from Lorraine Mulholland’s new book Saint Brigid and Other Amazing Irish Women

This is an excerpt from Lorraine Mulholland’s new book Saint Brigid and Other Amazing Irish Women