Former priest speaks out over Cardinal Keith O’Brien abuse

A former priest who has detailed allegations of abuse he suffered at the hands of the late Cardinal Keith O’Brien has warned that the Catholic Church is “blinded by its fear of scandal,” and has made little effort to establish the extent of his predatory sexual behaviour.

By Martyn McLaughlin | Sunday, 1st August 2021

Brian Devlin was one of four whistleblowers who detailed a litany of allegations against the man who was the Catholic Church’s most senior cleric in Britain, prompting his resignation and admission of sexual misconduct.

Eight years on, Devlin has spoken out for the first time about the man he considered a friend, mentor, and teacher, and outlined suggestions for reforms he believes could help end the “silence, secrets and omertà” in the church.

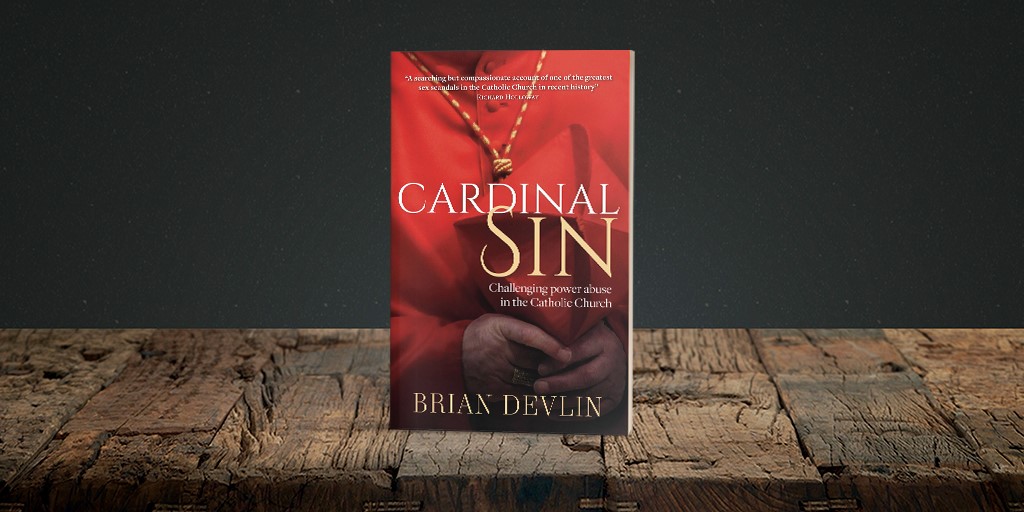

His book, ‘Cardinal Sin’, which chronicles the O’Brien affair and its fallout, has been hailed by Mary McAleese, the former Irish president, as a courageous insight into how the church’s hierarchical system protected O’Brien – who died aged 80 in 2018 – and other predatory clerics.

Cardinal Keith O’Brien. Photo: CNS

O’Brien was the spiritual director at Drygrange seminary, near Melrose where the teenage Devlin studied. He came to idolise the Northern Irishman, and they formed a close relationship.

One night towards the end of Devlin’s second year, he was praying with O’Brien in his bedroom. The two hugged, but the embrace was prolonged and intense. As Devlin turned to leave, O’Brien sat and pulled him on top of him.

“He began to caress me,” Devlin recalls in the book. “He told me that he loved me. At that point I was asking myself if he was joking. But then it became clear that he wasn’t.”

As embarrassment turned to shame and fear, Devlin left. When he woke the next morning, O’Brien was at his bedside. He leaned over, Devlin said, told him he had meant every word of what he had said, and apologised for his behaviour. Devlin forgave him, but came to the agonising realisation that his spiritual father was “a conman”.

Devlin bore that burden for years, plunging him into spiritual crisis while O’Brien ascended to a position of immense privilege and influence.

Only in 2010, when he began communicating with three serving priests, did he realise his story was not unique. The circle of four were strong, capable men. But what united them most, said Devlin, was the way O’Brien had left them diminished.

By February 2013, they decided to pursue an internal complaint against him, writing via an intermediary to Papal Nuncio Antonio Mennini, the Vatican’s ambassador to Britain.

The process coincided with the first papal resignation in almost 600 years. Amid silence around their complaint, and an indication Mennini already suspected something was amiss in the archdiocese, it emerged O’Brien would be heading to Rome to help appoint Benedict XVI’s successor. The confluence of events led the whistleblowers to the “nuclear option”.

Within 24 hours of The Observer detailing the allegations against O’Brien, he had resigned as the leader of the church in Scotland, and apologised to “all whom I have offended” during his ministry.

Author Brian Devlin

Last year, the Social Care Institute for Excellence published its independent safeguarding audit into the Archdiocese of St Andrews and Edinburgh. It noted an “outstanding and pressing need” for courageous leadership to foster open conversations about O’Brien’s actions.

Welcoming its publication, Archbishop Leo Cushley stressed the responsibility of all to ensure the church is a safe, welcoming place, and pointed to how safeguarding was a priority.

Devlin, however, was left with one abiding conclusion. “These men of privilege, feted for their rank, believe that it will all just magically disappear,” he said.

Looking back, the 61-year-old believes O’Brien’s confession to him was a means of “morally binding” him into silence. He has long since forgiven him, though he has been left exasperated by the church’s response.

“‘Scandal’ has a very significant meaning to the clergy,” he said. “The avoidance of it is the fig leaf that they use to cover up enormous harm.

“The true scandal wasn’t the publicity. It was the hypocritical sexual predation of O’Brien and the desire, in the full knowledge of that behaviour, by church leaders to quietly cover it up.”

It is telling that a section of Devlin’s book is titled ‘Where do we go? How do we heal?’; he asked himself those questions for years, having left the priesthood when it emerged O’Brien was to be ordained as his archbishop. He rebuilt his life, working with heroin addicts before joining the NHS, and is now married and living on the Black Isle.

The purpose of his book is not to shame the church. Rather, it is to help it renew itself around its core values, and inspire the laity to wrest a degree of control from the clergy. That, he admitted, requires not just theological reform – including the role of women in ministry – but cultural and behavioural renewal.

“If O’Brien’s story has taught us anything, it is that the ‘brotherhood of the priesthood’ – its exclusivity and its failure to embrace equality – is a danger to the church now,” he explained.

Devlin is mindful that in sharing his journey, he will not be the only one to feel pain. But in the absence of closure, he wants to ensure his narrative is on the record.

“I know by reigniting this story about O’Brien that they thought had gone away, it will cause some people hurt. But these things never go away unless you address them, and transparently and authentically pursue healing.”